Briefing note by ICSF (International Crimes Strategy Forum)[1] on the eve of the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, London

(Excel, 10-12 June 2014)

[PDF Download link in booklet form:

ICSF_booklet_14

The Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict is no doubt a laudable and timely initiative. We are, nevertheless, surprised by the fact that the stories of the sexual violence committed against Bengali girls and women during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971 despite its overwhelming scale and magnitude have not found a place in the summit. The decision to exclude the Bangladesh experience is one we can not support and we feel it is our responsibility to remind the organizers of the summit that the sacrifices of Bengali girls and women during the war of 1971 were one of the goriest of the 20th century.

In 1971, core international crimes of the likes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed against the Bengali populace. During the course of the war 10 million people fled across the border into India as refugees.[2] The Pravda, in January 1972 reported the loss of three million lives at the hands of the invading Pakistan army.[3] A correspondent of the Times in ‘Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal’ quoted a US official admitting that what the Bengalis had endured was ‘the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland’.[4]

The occupying Pakistani military and its local auxiliaries in the form of the Peace Committees, Razakar, Al Badr and Al Shams forces specifically targeted among others, the Bengali girls and women of Bangladesh. The overarching objective, irrespective of the outcome of the war, was to ensure the presence of the Punjabi (i.e., Pakistani) imprint or ‘gene’ so to speak on the future generations of the Bengalis, the consequence of which rape and other forms of sexual violence was used as weapons of war.

The late Acher K Blood, the U.S. Consul General based in Dhaka at the time, sent a series of secret telegrams to the highest officials of the American government informing them of the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army during and immediately following Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971. Describing how the dormitory of female students at Dhaka University was attacked, Blood wrote: “Rokeya Hall, a dormitory for girl students, was set ablaze and the girls were machine-gunned as they fled the building. The attack seemed to to be aimed at eliminating the female leadership since many girl student leaders resided in that hall.”[5]

The policy of raping and murder of Bengali women and girls continued throughout the war which lasted nine months. Incidents of hundreds of Bengali women being held captive inside military brothels run by the Pakistan military were reported in the international media at the time.[6]

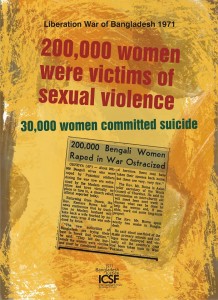

Reverend Kentaro Buma an Asian Relief Secretary for the World Council of Churches learned first hand the state of affairs during a two-week mission in war torn independent Bangladesh. Upon his return to Geneva, Buma on January 17, 1972 held a press conference where he informed 200,000 women had been raped by Pakistani soldiers and they were now being ostracized by the predominantly conservative Bengali community.[7] A War Rehabilitation Organization led by Justice K.M. Sobhan had been formed in war-torn Bangladesh. Maleka Khan, one of the many social workers assisting the rehabilitation process had herself read depositions of more than 5,000 women who had been sexually violated.[8] Geoffrey Davis, a medical graduate from Australia, arrived in Bangladesh in March 1972 under the auspices of International Planned Parenthood, the UNFPA and the WHO.[9] Davis stayed in Bangladesh for six months during which he conducted numerous abortions and at the same time offered training on proper abortion procedures and techniques.[10] His experiences led him to conclude that the government estimate of 200,000 rapes was a conservative one. Davis interviewed many Pakistani POWs who were behind bars at a prison in Comilla.[11] These interviews revealed that they were under instructions from the top brass of the Pakistan army that a good Muslim was duty bound to fight anyone other than his father.[12] This prompted them to impregnate as many Bengali women as they could so that there would be a whole generation of children in East Pakistan would be born with West Pakistani blood.[13]

The government of the newly independent State was determined to provide justice to the millions who had suffered at the hands of the Pakistani military and their local auxiliaries. Two pieces of legislation were produced in quick succession to try persons against whom there were allegations of committing wartime offences. On March 28, 1972, the trials of local Bengalis immediately ensued in 73 tribunals all over Bangladesh under the Bangladesh Collaborators (Special Tribunals) Order, 1972.[14] Prevailing all odds, by October 31, 1973 out of the 37,471 accused, the trials of 2,848 persons were completed. 752 persons were convicted and sentenced and the remaining 2,096 persons received acquittals.[15] Out of the convictions one person received the death penalty.[16]

The Bangladesh Government on March 25, 2010 for the purposes of the ‘detention, prosecution and punishment of persons responsible for committing genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and other crimes under international law’ announced the constitution of the first International Crimes Tribunal under the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973. The second International Crimes Tribunal (ICT-2) was established on March 22, 2012. Till date, the Tribunals have handed down a total of nine verdicts.

Although, the charges and verdicts against the accused under the Bangladesh Collaborators Special Tribunals and the International Crimes Tribunals did not shed specific focus on the targeted raping and killing of Bengali women and girls during the Liberation War of 1971, a regrettable trend that is also somewhat typical of other international tribunals, some of the accused before the Tribunals have been found guilty for committing the crime of rape. For instance, in cases, The Chief Prosecutor Versus Delowar Hossain Sayeedi[17] and The Chief Prosecutor Versus Abdul Quader Molla[18], the accused were found guilty by the International Crimes Tribunal of committing rape as a crime against humanity.

The organizers of the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict 2014 has claimed that it is “the largest gathering ever brought together on the subject, with a view to creating irreversible momentum against sexual violence in conflict and practical action that impacts those on the ground.”[19] Our questions to the organizers are unambiguous and simple: Were the stories of sufferings of countless Bengali girls and women during 1971 not worth telling at the global summit? Don’t the Bengali victims of sexual violence deserve to be recognised and rehabilitated by the world community? When it comes to acknowledging immeasurable crimes committed four decades ago, of all things, time is not on our side.

[NOTE: If you have any query regarding this briefing note, please email us at info@icsforum.org . We will be happy to respond to any query and provide further references in support]

REFERENCES:

[1]www.icsforum.org. Operating from more than 30 cities around the world, International Crimes Strategy Forum (ICSF) is an independent global coalition and network of activists, experts and academics. The network is committed to support justice initiatives and campaigns that are aimed at the serious international crimes perpetrated by the Pakistani armed forces and their local collaborators during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. United the coalition stands against all forms of impunity. Contact email: info@icsforum.org

[2]‘Tears of Bangladesh: Refugees of 1971 through Journalist’s Eyes’ (Graffiti, 13 June 2013) < http://midnightowlblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/tears-of-bangladesh-1971-refugees.html > accessed 22 January 2014; David Myrad, ‘Sadruddin Aga Khan and the 1971 East Pakistani Crisis’ (2010) Global Migration Research Paper, 6 < http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/globalmigration/shared/Publications/Global%20Migration%20Research%20Paper%202010%20N1.pdf > accessed 22 January 2014.

[3]With regard to the figure 3 million, Ziauddin Ahmed in 1996 wrote: “This figure has been widely accepted to be nearer to the exact number of casualties. No systematic efforts have yet been made to determine the extent of the genocide.” please see Ziauddin Ahmed, ‘The Case of Bangladesh: Bringing to Trial the Perpetrators of the 1971 Genocide’ 109 (n 105); R.J. Rummel, Death by Government (3rd edn, Transaction Publishers 2002).

[4]‘Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal’ Time, (2 August 1971) <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878408-3,00.html > accessed 22 January 2014.

[5]Archer K Blood, The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh – Memoirs of an American Diplomat (The University Press Limited, 2002) p. 207.

[6]See the Time magazine report dated October 25, 1971.

[7]‘200,000 Bengali Women Raped in War Ostracized’ Lawrence Daily Journal (Geneva, 17 January 1972) <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2199&dat=19720117&id=ayUzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=H-cFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5897,1725550 > accessed 22 January 2014; ‘200,000 Raped Bengali Wives Ostracized’ Sarasota Journal (Geneva, 19 January 1972) <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1798&dat=19720119&id=OB8eAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Go0EAAAAIBAJ&pg=5551,3070792 > accessed 22 January 2014; Susan Brownmiller, Against our Will Men, Women and Rape (1st edn, Secker & Warburg 1975).

[8]Shahriar Kabir, The Intolerable Sufferings of Seventy One (Dhaka Kazi Mukul 2009).

[9]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[10]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[11]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[12]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[13]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[14]Promulgated on 24 January, 1972 (P.O. Order No. 8 of 1972).

[15]Syeed Ahamed, ‘Trials and Errors’ (icsforum.org, 30 September 2010) <http://icsforum.org/blog/syeed/trials-and-errors/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[16]On June 9, 1972, a Special Tribunal in Kushtia sentenced Chikon Ali to death. A former Razakar, Ali was found guilty of collaborating with the Pakistan army.

[17]http://www.ict-bd.org/ict1/ICT1%20Judgment/sayeedi_full_verdict.pdf

[18]http://www.ict-bd.org/ict2/ICT2%20judgment/quader_full_verdict.pdf

[19]https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/sexual-violence-in-conflict

Briefing note by ICSF (International Crimes Strategy Forum)[1] on the eve of the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict, London

[PDF Download link in booklet form: ICSF_booklet_14(Excel, 10-12 June 2014)

The Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict is no doubt a laudable and timely initiative. We are, nevertheless, surprised by the fact that the stories of the sexual violence committed against Bengali girls and women during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971 despite its overwhelming scale and magnitude have not found a place in the summit. The decision to exclude the Bangladesh experience is one we can not support and we feel it is our responsibility to remind the organizers of the summit that the sacrifices of Bengali girls and women during the war of 1971 were one of the goriest of the 20th century.

In 1971, core international crimes of the likes of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity were committed against the Bengali populace. During the course of the war 10 million people fled across the border into India as refugees.[2] The Pravda, in January 1972 reported the loss of three million lives at the hands of the invading Pakistan army.[3] A correspondent of the Times in ‘Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal’ quoted a US official admitting that what the Bengalis had endured was ‘the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland’.[4]

The occupying Pakistani military and its local auxiliaries in the form of the Peace Committees, Razakar, Al Badr and Al Shams forces specifically targeted among others, the Bengali girls and women of Bangladesh. The overarching objective, irrespective of the outcome of the war, was to ensure the presence of the Punjabi (i.e., Pakistani) imprint or ‘gene’ so to speak on the future generations of the Bengalis, the consequence of which rape and other forms of sexual violence was used as weapons of war.

The late Acher K Blood, the U.S. Consul General based in Dhaka at the time, sent a series of secret telegrams to the highest officials of the American government informing them of the atrocities committed by the Pakistan army during and immediately following Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971. Describing how the dormitory of female students at Dhaka University was attacked, Blood wrote: “Rokeya Hall, a dormitory for girl students, was set ablaze and the girls were machine-gunned as they fled the building. The attack seemed to to be aimed at eliminating the female leadership since many girl student leaders resided in that hall.”[5]

The policy of raping and murder of Bengali women and girls continued throughout the war which lasted nine months. Incidents of hundreds of Bengali women being held captive inside military brothels run by the Pakistan military were reported in the international media at the time.[6]

Reverend Kentaro Buma an Asian Relief Secretary for the World Council of Churches learned first hand the state of affairs during a two-week mission in war torn independent Bangladesh. Upon his return to Geneva, Buma on January 17, 1972 held a press conference where he informed 200,000 women had been raped by Pakistani soldiers and they were now being ostracized by the predominantly conservative Bengali community.[7] A War Rehabilitation Organization led by Justice K.M. Sobhan had been formed in war-torn Bangladesh. Maleka Khan, one of the many social workers assisting the rehabilitation process had herself read depositions of more than 5,000 women who had been sexually violated.[8] Geoffrey Davis, a medical graduate from Australia, arrived in Bangladesh in March 1972 under the auspices of International Planned Parenthood, the UNFPA and the WHO.[9] Davis stayed in Bangladesh for six months during which he conducted numerous abortions and at the same time offered training on proper abortion procedures and techniques.[10] His experiences led him to conclude that the government estimate of 200,000 rapes was a conservative one. Davis interviewed many Pakistani POWs who were behind bars at a prison in Comilla.[11] These interviews revealed that they were under instructions from the top brass of the Pakistan army that a good Muslim was duty bound to fight anyone other than his father.[12] This prompted them to impregnate as many Bengali women as they could so that there would be a whole generation of children in East Pakistan would be born with West Pakistani blood.[13]

The government of the newly independent State was determined to provide justice to the millions who had suffered at the hands of the Pakistani military and their local auxiliaries. Two pieces of legislation were produced in quick succession to try persons against whom there were allegations of committing wartime offences. On March 28, 1972, the trials of local Bengalis immediately ensued in 73 tribunals all over Bangladesh under the Bangladesh Collaborators (Special Tribunals) Order, 1972.[14] Prevailing all odds, by October 31, 1973 out of the 37,471 accused, the trials of 2,848 persons were completed. 752 persons were convicted and sentenced and the remaining 2,096 persons received acquittals.[15] Out of the convictions one person received the death penalty.[16]

The Bangladesh Government on March 25, 2010 for the purposes of the ‘detention, prosecution and punishment of persons responsible for committing genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and other crimes under international law’ announced the constitution of the first International Crimes Tribunal under the International Crimes (Tribunals) Act, 1973. The second International Crimes Tribunal (ICT-2) was established on March 22, 2012. Till date, the Tribunals have handed down a total of nine verdicts.

Although, the charges and verdicts against the accused under the Bangladesh Collaborators Special Tribunals and the International Crimes Tribunals did not shed specific focus on the targeted raping and killing of Bengali women and girls during the Liberation War of 1971, a regrettable trend that is also somewhat typical of other international tribunals, some of the accused before the Tribunals have been found guilty for committing the crime of rape. For instance, in cases, The Chief Prosecutor Versus Delowar Hossain Sayeedi[17] and The Chief Prosecutor Versus Abdul Quader Molla[18], the accused were found guilty by the International Crimes Tribunal of committing rape as a crime against humanity.

The organizers of the Global Summit to End Sexual Violence in Conflict 2014 has claimed that it is “the largest gathering ever brought together on the subject, with a view to creating irreversible momentum against sexual violence in conflict and practical action that impacts those on the ground.”[19] Our questions to the organizers are unambiguous and simple: Were the stories of sufferings of countless Bengali girls and women during 1971 not worth telling at the global summit? Don’t the Bengali victims of sexual violence deserve to be recognised and rehabilitated by the world community? When it comes to acknowledging immeasurable crimes committed four decades ago, of all things, time is not on our side.

[NOTE: If you have any query regarding this briefing note, please email us at info@icsforum.org . We will be happy to respond to any query and provide further references in support]

REFERENCES:

[1]www.icsforum.org. Operating from more than 30 cities around the world, International Crimes Strategy Forum (ICSF) is an independent global coalition and network of activists, experts and academics. The network is committed to support justice initiatives and campaigns that are aimed at the serious international crimes perpetrated by the Pakistani armed forces and their local collaborators during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. United the coalition stands against all forms of impunity. Contact email: info@icsforum.org

[2]‘Tears of Bangladesh: Refugees of 1971 through Journalist’s Eyes’ (Graffiti, 13 June 2013) < http://midnightowlblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/06/tears-of-bangladesh-1971-refugees.html > accessed 22 January 2014; David Myrad, ‘Sadruddin Aga Khan and the 1971 East Pakistani Crisis’ (2010) Global Migration Research Paper, 6 < http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/globalmigration/shared/Publications/Global%20Migration%20Research%20Paper%202010%20N1.pdf > accessed 22 January 2014.

[3]With regard to the figure 3 million, Ziauddin Ahmed in 1996 wrote: “This figure has been widely accepted to be nearer to the exact number of casualties. No systematic efforts have yet been made to determine the extent of the genocide.” please see Ziauddin Ahmed, ‘The Case of Bangladesh: Bringing to Trial the Perpetrators of the 1971 Genocide’ 109 (n 105); R.J. Rummel, Death by Government (3rd edn, Transaction Publishers 2002).

[4]‘Pakistan: The Ravaging of Golden Bengal’ Time, (2 August 1971) <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,878408-3,00.html > accessed 22 January 2014.

[5]Archer K Blood, The Cruel Birth of Bangladesh – Memoirs of an American Diplomat (The University Press Limited, 2002) p. 207.

[6]See the Time magazine report dated October 25, 1971.

[7]‘200,000 Bengali Women Raped in War Ostracized’ Lawrence Daily Journal (Geneva, 17 January 1972) <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2199&dat=19720117&id=ayUzAAAAIBAJ&sjid=H-cFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5897,1725550 > accessed 22 January 2014; ‘200,000 Raped Bengali Wives Ostracized’ Sarasota Journal (Geneva, 19 January 1972) <http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1798&dat=19720119&id=OB8eAAAAIBAJ&sjid=Go0EAAAAIBAJ&pg=5551,3070792 > accessed 22 January 2014; Susan Brownmiller, Against our Will Men, Women and Rape (1st edn, Secker & Warburg 1975).

[8]Shahriar Kabir, The Intolerable Sufferings of Seventy One (Dhaka Kazi Mukul 2009).

[9]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[10]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[11]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[12]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[13]Bina D’Costa, ‘1971: Rape and its consequences’ bdnews24.com <http://opinion.bdnews24.com/2010/12/15/1971-rape-and-its-consequences/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[14]Promulgated on 24 January, 1972 (P.O. Order No. 8 of 1972).

[15]Syeed Ahamed, ‘Trials and Errors’ (icsforum.org, 30 September 2010) <http://icsforum.org/blog/syeed/trials-and-errors/ > accessed 22 January 2014.

[16]On June 9, 1972, a Special Tribunal in Kushtia sentenced Chikon Ali to death. A former Razakar, Ali was found guilty of collaborating with the Pakistan army.

[17]http://www.ict-bd.org/ict1/ICT1%20Judgment/sayeedi_full_verdict.pdf

[18]http://www.ict-bd.org/ict2/ICT2%20judgment/quader_full_verdict.pdf

[19]https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/sexual-violence-in-conflict

you might also like

Protest-event of ICSF with 21 allied organisations in front of Turkish Embassy London

২ ফেব্রুয়ারী ২০১৩ মতবিনিময় সভা: পক্ষশক্তির কর্মসূচীর রূপরেখা

লন্ডনে আইসিএসএফ এর মতবিনিময় সভা: প্রসঙ্গ ১৯৭১ এর পক্ষশক্তির কর্মসূচীর রূপরেখা